Lolly Willowes: A witch for our times

On reading Sylvia Townsend Warner's 1926 novel about a witch.

Merry Christmas! I am four champagnes and one enormous Christmas lunch-dinner in. My child is asleep, the house is quiet… and Boxing Day, the most sacred day of the year, is ahead. Bliss. So, here is an essay about a novel about a witch, just because (four champagnes). I wrote it earlier in the year to exorcise the grip that Lolly Willowes had on my mind. It didn’t really work. I keep thinking about it and Sylvia Townsend Warner. The below is a bit English Lit 101 but has helped me tease out some of the things I love about the novel and that keep me wondering. I’m trying to find my way into STW’s work (a ton of reading - she was prolific!) and think I’m starting to get there. This is an early adventure in what might be quite an Odyssey.

I read Sylvia Townsend Warner’s first novel Lolly Willowes (1926) the day before Aotearoa went into lockdown in 2020. I read it in Castle Point, that magical elbow of land where the sand and sky and lighthouse look as though they have been composed by the same celestial hand. I lay on the window seat and stole time. I read the novel cover to cover, ignoring the news, quickly realising that I was in the company of no ordinary writer and no ordinary story. I could feel the book’s magic working through me, making tweaks and pulling threads. The next day we walked to the lighthouse and stared at the wide sea. Then we got back in the car to drive back to Wellington so we could lockdown with everyone else. Sylvia and her idiosyncratic witch travelled back with me and has hung about the house ever since. Only now they are staking out a far larger chunk of real estate in my mind than I had bargained for. Lolly Willowes is the witch of my days from a book for our times.

At the start of Lolly Willowes, the world has been warped by the First World War and yet, once it is over, Laura (Lolly) notices ‘all around her once more the familiar undisturbed shadows of familiar things’. For Lolly, a spinster aunt, the War had made her life of relentless domestic-based care even more exhausting. After years of ‘doing up parcels’ conscious that ‘blood was being shed for her’, on Armistice day 1918 Laura becomes so sick with the flu that she ‘was enabled to stay in bed for a fortnight, a thing she had not done since she came to London’. Laura is physically undone by the past four years and psychologically she is fundamentally changed. For her family, on the other hand, she observes, ‘it was astonishing what little difference differences had made’; ‘They, she thought, had done with the war, whereas she had only shelved it, and that by an accident of consciousness.’

One hundred years on, Sylvia’s novel about a post-War World reflects, albeit at a slant, a pandemic state of mind. At a child’s birthday party this year, I had to intercept my son who was careering through a playground so that I could administer his asthma medication. Since contracting Covid he’s had a chronic cough and is prone to wheezing and hacking whenever the air is crisp. Several other parents at the party reported the same thing. And yet, there we all were, tucking into trays of jet planes and popcorn and cake, and passing parcels, like it was the 80s. Our adult conversation couldn't help but veer towards the pandemic and our swarm of barely-alive year olds with their unblinking acceptance of masked adults, their use of the words ‘covid’, ‘pandemic’ (or ‘armageddon’ in my son’s case). The small details of everyday life look the same as they did pre-Covid but everything is different.

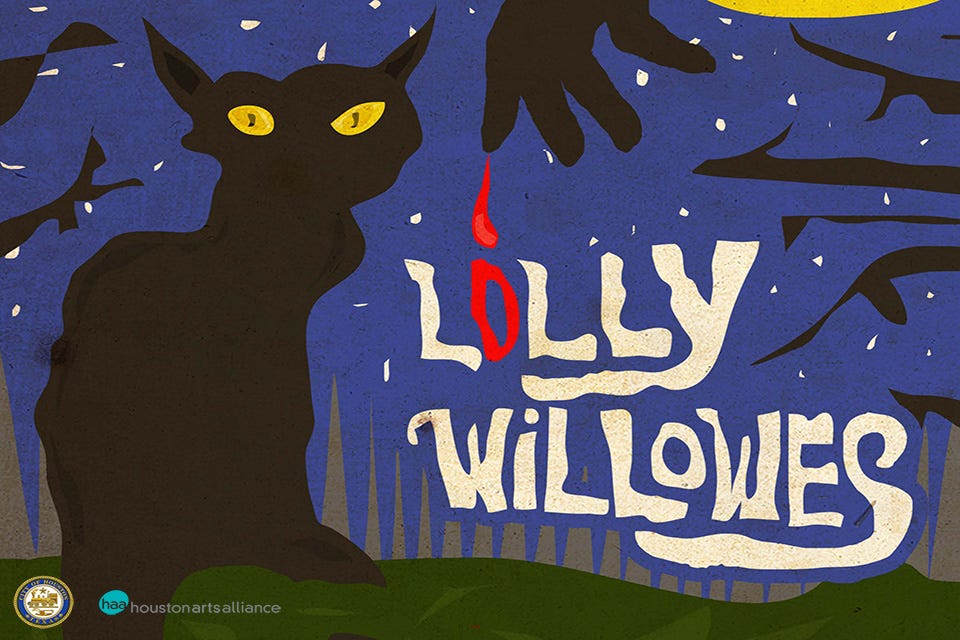

Adore this poster art for a musical theatre adaptation of LW (details here). The blood! Lolly’s cat’s name is Vinegar and in the novel their meeting scene is bloody and delicious.

At the beginning of Part II of the novel, Laura is struck by a creeping restlessness. It is Autumn and the deadening of leaves, the stripping of trees, the bright cold moon speak to her with a fresh urgency. She tries to attribute her ‘recurring autumnal fever’ to anxiety over growing older. But it isn’t that. She seeks clues to her unrest in ‘the jostling tombstones at Bunhill Fields’ and ‘among the City churches’ and in ‘the goods-yard of the G.W.R.’: ‘She liked to think of the London of Defoe’s Journal, and to fancy herself back in the seventeenth century, where, so it seemed to her, there were still darknesses in men’s minds.’

The Journal is A Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722. It’s a harrowing read full of vivid images of human carnage in City streets ravaged by a merciless disease. The book offers Laura a portal through which to ‘ramble in strange places of the mind’. The book meets her where the stifling decorum of her family and a forgetful middle class society do not.

It struck me – when my partner and I, along with the entire world it seemed, settled in for the marathon final episodes of Stranger Things – that a gory TV show is to me what A Journal of the Plague Year is to Laura. I am apparently hungry for a world in which blood is spilled, flesh is torn apart, bones are cracked, and eyes are popped out of their sockets and nobody seems to know where their children are while streets and homes are ravaged by a violent serial killer. The show is charming for its nostalgia and satisfying for its head-on acknowledgement of how grotesque the real world can be: the psychotic bullies, the threat of war, the sickening prejudices. In Stranger Things the characters are lured into psychological caves and chased through the terrifying corners of their own minds. And we savour every second of it and the 80s child heroes who we think remind us of ourselves. In the same way that Defoe’s Journal validates Laura’s cravings, Stranger Things is the comfort-horror we need to relieve, even if temporarily, the real horrors that we know are out there but that we can’t seem to contain or control.

As an antidote for her hunger for ‘darknesses’, Laura creates a ritual for cheering up: a habit of small indulgences that give her pleasure, like ‘a sort of mental fur coat’. These include buying roasted chestnuts to eat at home in her bedroom; visiting second-hand bookshops; getting the expensive soaps; having sumptuous afternoon teas; and bringing home unseasonable hot-house flowers.

My fur-coat policy since March 2020 is still in good use, if not developing in strength and frequency. Between episodes of Stranger Things I blithely purchase the expensive hand-soap for the bathroom, the stuff that smells so good that it really does issue a scent as sharp as a sword against a blue, world-weary mood.

Sylvia Townsend Warner.

By Winter 1921 Laura is done. The ‘war is safely over’ and ordinary life reasserts itself with accumulated weddings, graduations, births, and ups and downs on the still-volatile Stock Exchange. While Laura’s family appears to be thriving, she herself is undergoing some kind of transformation. In a shop, ‘half florist and half greengrocer’, she has a vision of herself ‘standing alone in a darkening orchard, her feet in the grass, her arms stretched up to the pattern of leaves and fruit, her fingers seeking the rounded ovals of the fruit among the pointed ovals of the leaves.’ Laura comes-to when the grocer (later we understand that he’s actually Satan) asks her what she’d like: ‘I want one of those large chrysanthemums,’ she said. The grocer wraps the flowers up and throws in a spray of beech leaves. When Laura catches their scent, the question that had been oscillating inside of her is finally answered: ‘they smelt of woods, of dark rustling woods like the wood to whose edge she came so often in the country of her autumn imagination.’ The grocer tells Laura that the beech is from Great Mop, a village in the Chilterns where his sister lives. Laura needs no further information. It is decided. That is where she must go; no further clues are required.

In the novel, Great Mop represents a kind of utopia. In this bucolic hideaway nobody really cares what you do and what you don’t. The village enables a gentle unravelling of City habits and a creeping expansion of the true self. In this place Lolly re-wilds herself. She sleeps outside, sleeps for days if she needs, and untangles from London and the draining patterns of her old life. Laura pleases herself.

It is when her nephew, Titus, barges in on her sweet, slow existence at Great Mop, full of his male ego, confidence and noise, that Lolly’s dormant witchcraft comes into play. Titus, she knows, ‘mean[s] her nothing but good’, but his presence overwhelms her quiet ways, her newfound and particular relationship with her environment. He is an extrovert in an introvert’s world. His love has its foundation in values of domination and control. Or, as Warner puts it, it was a ‘possessive and masculine love … He loved the countryside as though it were a body.’

It is the desperate need to rid herself of this suffocating family member, this beacon of threat to female autonomy, that draws out Lolly’s witchcraft. Soon after Titus’ unwelcome intrusion, she finds herself in the company of another unexpected creature: a small, black kitten. Immediately it attacks her with a ferocity that ends with bloody scratches and a realisation: ‘The kitten was her familiar spirit, that already had greeted its mistress, and sucked her blood … Nursing the kitten in her lap Laura sat thinking. Her thoughts were of a different colour now.’ Now armed with a witch’s familiar to bolster her resolve, Lolly toys with Titus’ daily milk, souring it. Lolly the newfound witch curdles his small comforts until he is driven out and she is free once more.

There is a quiet fury in Lolly Willowes. To live as she chooses is Laura’s deepest desire. The reversal of Roe v Wade hooked this story world back into our current one, once again. This is a book about a woman’s right to herself, her body, her space. It is about the process of disentanglement from a man’s world: the built environments, the trappings of time-based living, the systems and violent catastrophes. Lolly revolts. She leaves behind the people who tax her time and energy with their needs and takes herself into a landscape that can enable her body, and with it her inner self, to sprawl.

There are so many passages in Lolly Willowes that stun with clarity and invention. But among my favourite passages are those with Satan in them. At first the devil hides in plain sight: he’s the grocer, then the gardener. But by the end of the book Lolly has his number. The final chapter centres on a long and complex meeting between them: they sit together on the grass, in an elaborately designed garden/memorial gravesite called Maulgrave’s Folly (brilliant name) in the Chilterns, and hash a few things out. Lolly pours out her longest monologue, an impassioned treatise on the wasted lives of women. Satan listens with patience and a distance respect: ‘The Devil was silent, and looked thoughtfully at the ground. He seemed to be rather touched by all this.’ Encouraged, Lolly keeps going and offers that ‘for so many, what can there be but witchcraft? … Even if other people still find them quite safe and usual, and go on poking with them, they know in their hearts how dangerous, how incalculable, how extraordinary they are.’ It’s a rousing speech and a fascinating cry for the inner worlds of women: infused with a hidden power even when they are at their most powerless.

Their final meeting is a beguiling scene with so much more to it that I can write here. What keeps pulling me back is the idea of gardens/woods as a site for devilish exchange; Satan’s elusiveness; and Lolly’s outpourings – her fully fledged confidence and release. The final line of the novel always gives me pause: ‘... he [Satan] would not disturb her. A closer darkness up on her slumber, a deeper voice in the murmuring leaves overhead – that would be all she would know of his undesiring and unjudging gaze, his satisfied but profoundly indifferent ownership.’ At first it’s thrilling, to know that Lolly can now truly live as she chooses. But the gaze still remains and that is more than a little haunting. Is the Devil a feminist? Is witchcraft, where Satan is the boss, a patriarchy by definition?

Sylvia Townsend Warner is enjoying a renaissance since the reissue of her novels. I recently talked with the writer Clementine Ford who is working on a book about the ways in which marriage is detrimental to women. ‘I want this book to break up marriages, and then stop women from marrying at all.’ she said. I wanted to unleash upon Clementine my appreciation for Sylvia Townsend Warner as the OG escape artist: Sylvia was a committed communist; she lived with the love of her life, Valentine Ackland, at a precarious time to be openly queer; and she wrote this novel, her very first, about a witch of cottage-core, anti-capitalist, feminist dreams.

Ultimately, in many ways, Lolly Willowes speaks to metamorphosis born from exhaustion. That also feels very now. Many of us might recognise Lolly’s autumnal fever. The craving of darknesses: horrors to offset horrors. News of floods, fire, war, the multiplicity of reversals of women’s rights, the climate clock. It is a perilous and exhausting time. The work of this novel is to coax out our capacity to fight against what appears to be immovable: to suggest there is a dormant magic inside of us, if we would only follow it.